Monarch Malaise

Wednesday, November 15th, 2017This is Passport to Texas

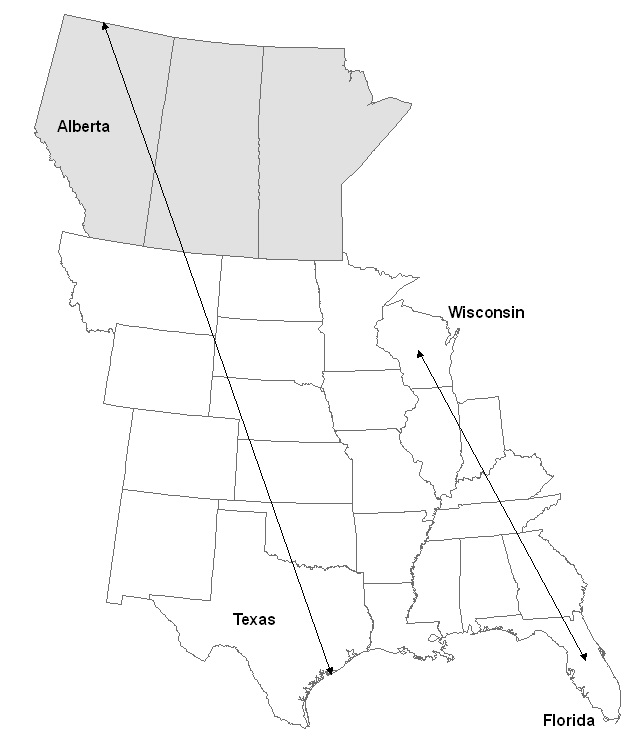

Habitat loss along its migration route may be one reason the Monarch butterfly is in decline. While feeding on nectar, Monarchs pollinate wildflowers along their route, which benefits our ecosystem.

There are two primary ways that habitat supports pollinators.

Johnnie Smith oversees outreach and education at Texas Parks and Wildlife.

And one is, the adult pollinators oftentimes feed on nectar of flowers. So, flowering plants that are a food source for the pollinator is very important. But also, is the food source that the pollinator’s larvae rely on as they’re growing up and becoming an adult. And so, that is just as important as the flowering plants that support the adults.

For Monarchs, native milkweed is an important plant. By cultivating them in our yards, along with other nectar and larval plants, we can all play a part in their survival.

There is no effort that is too small to be counted worthy. And there’s no spot of land that is too small to contain pollinator habitat. So, we really want to empower everybody—tht they can make a difference. Right where you stand. Right where you live—you can crate pollinator habitat, and help turn around this negative trend with the monarchs.

Find native and adapted plants for pollinators on the Texas Parks and Wildlife website.

The Wildlife Restoration program supports our series.

For Texas Parks and Wildlife…I’m Cecilia Nasti.

Passport to Texas is a

Passport to Texas is a  Passport to Texas is made available by:

Passport to Texas is made available by: