How to Spot the Cactus Moth

Wednesday, July 18th, 2018

Photo credits: (top) Susan Ellis, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org; (mid) Jeffrey W. Lotz, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org; (bottom) CMDMN

This is Passport to Texas

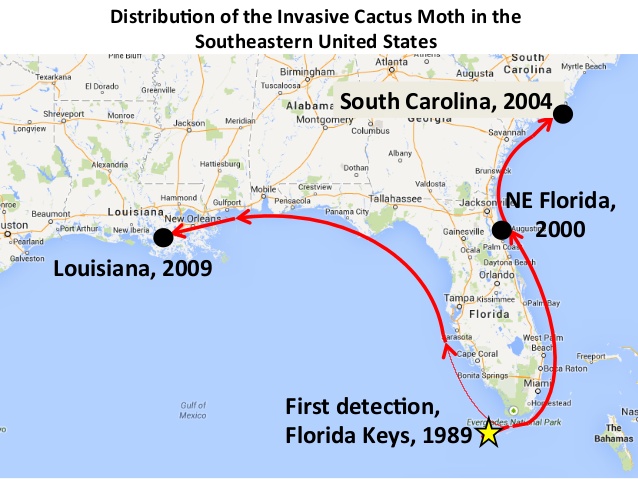

Prickly pear cacti are economically important to Texas and Mexico. They’re also the larval food of the cactus moth, a nonnative species that’s heading to Texas.

Invertebrate biologist Michael Warriner says the larvae of this prolific South American moth species, which is active this time of year, can decimate prickly pear populations. The adult insect is non-descript and difficult to identify, but the larvae is easier to recognize.

Looking for the larvae or evidence of feeding damage is the best thing to look for. The caterpillars themselves are a bright orange to red coloration with black bands or spots. The larvae spend most of their time inside of the prickly pear pad, and they basically hollow it out. So the pad, as the larvae feed on it, will become transparent and they’ll eventually just collapse.

Researchers are developing methods of managing the moth. Until then, if you see infested plants…

You can still control it by removing the infested pads and that would help. Disposing and burning them. Or simply enclosing them in some kind of plastic bag to heat up the larvae and kill them.

Find links to more information about the cactus moth at passporttotexas.org.

The Wildlife Restoration program supports our series.

For Texas Parks and Wildlife…I’m Cecilia Nasti

Passport to Texas is a

Passport to Texas is a  Passport to Texas is made available by:

Passport to Texas is made available by: