Down with Donax

Friday, May 4th, 2018This is Passport to Texas

Texas Parks and Wildlife rolled out a new campaign on management of an invasive grass called Arundo Donax.

Angela England, an aquatic invasive species biologist, says learn to recognize the plant; say something if you see it, and be aware of its presence.

A lot of it you’ll see on the right-of-ways of the roads—but also in the creeks and rivers. On the banks.

The program reaches out to people in construction and road maintenance. The most effective management is herbicide use.

It doesn’t spread by seed. It only spreads by fragments of the roots and stems. So, any time there is construction activity, or veg management with mowing or tilling that will create these new fragments and spread them around—that’s just creating whole new patches that will be a problem later.

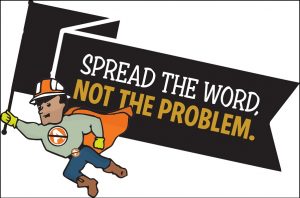

Monica McGarrity, aquatic invasive team leader says the campaign employs a character called Arundo Control Man—an everyday hero.

Everyone can be an Arundo control hero. Everyone can help to manage it. This is a training program that we’re asking everyone to put into play for their safety trainings; it’s plug and play. You can order brochures from us online. You can click play on the video, and train these groups so that all of them can become Arundo control heroes. And that’s what we’re trying to encourage.

Find a link to additional resources at passporttotexas.org.

The Wildlife Restoration program supports our series.

For Texas Parks and Wildlife, Cecilia Nasti.

Passport to Texas is a

Passport to Texas is a  Passport to Texas is made available by:

Passport to Texas is made available by: