So Much Sargassum

Monday, March 19th, 2018This is Passport to Texas

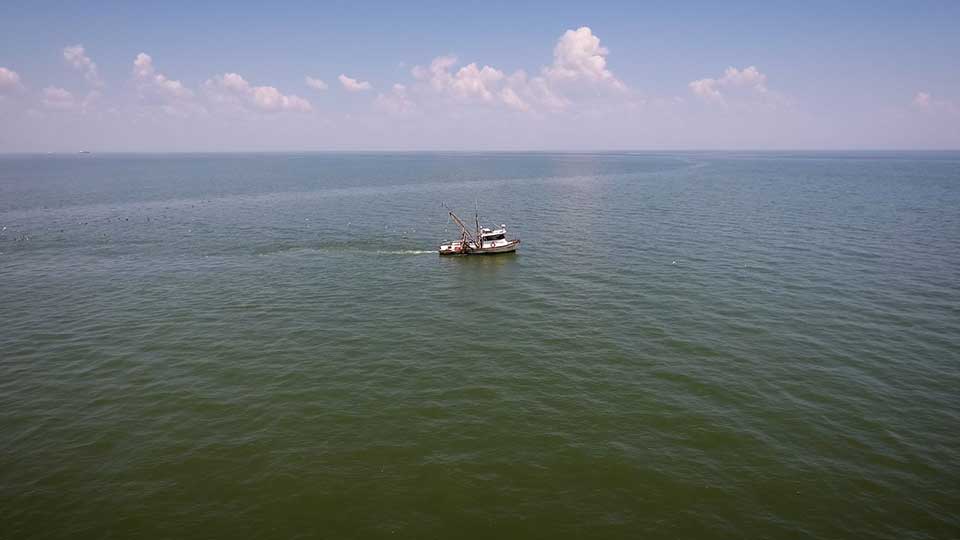

Every spring and summer, visitors to the coast encounter piles of brown, wet, slimy vegetation on Texas beaches.

It’s a brown algae called sargassum.

Paul Hammerschmidt, formerly with Coastal Fisheries, says sargassum may accumulate on tide lines for miles.

It belongs to a whole group of plants that belong to the sargassum group. Most of those plants are attached to hard substrate – rocks, shells – that kind of thing. These particular species don’t attach to anything; they’re floating. They have little tiny gas bladders that help the plant float. So, periodically that breaks away and ends up on the Texas beach.

Sargassum originates in the Sargasso Sea, in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean.

…in a big floating gyre; a gyre is a big eddy. And this particular sea has no shoreline at all – no land shoreline. It’s surrounded by four different ocean currents that keep that seaweed trapped in this one particular area.

Yet, tons of sargassum escape and end up on Texas shores.

Changes in the currents; winds and storms can occur in the area, and section of it actually break off and get into the main currents. Those main currents will bring them into the gulf and eventually onto the beaches.

Tomorrow: the value of sargassum.

The Sport Fish Restoration program supports our series.

For Texas Parks and Wildlife…I’m Cecilia Nasti.

Passport to Texas is a

Passport to Texas is a  Passport to Texas is made available by:

Passport to Texas is made available by: